Making Security Pay (sidebar)

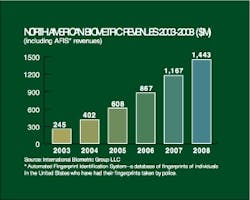

Less than 10 percent of all industrial facilities today make use of biometrics for employee identification or verification, industry experts estimate. But the technology is definitely on the rise, most agree. International Biometric Group LLC, a New York-based consulting and market research firm, projects that the North American market for biometrics hardware and software will grow to more than $1.4 billion by 2008, up from $402 million last year.

Biometrics technologies have been on the market for a number of years. “I think the biggest selling point for biometrics today is that the technology has finally gotten to the point where, number one, it works, and number two, you can afford it. It no longer costs an arm and a leg to have this type of system operating,” observes Roy Bordes, president and chief executive officer of The Bordes Group Inc., an Orlando, Fla., security engineering and design firm.

Biometrics technology works by measuring unique physical characteristics of an individual —such as a fingerprint, hand geometry, voice pattern or eye structure—as a way to confirm identity. When an individual enrolls in a program, a digital template is created that stores the characteristics of the biometric, which can later be compared to the individual for identification.

Biometric templates can be stored on traditional access cards often used for building access. But the growing use of microprocessor-based smart cards, which typically have a larger memory capacity for storing sometimes hefty biometric templates, is helping boost use of biometrics, says Mark Peterson, director, iTechnology Design Resource Group, for HID Corp., an Irvine, Calif., maker of access control cards and readers.

In many cases, biometrics are used not to identify an individual, but rather to verify identity—to be sure that the individual using an access card is indeed the individual to whom the card was issued, Peterson says. This is because the verification process—comparing, say, the fingerprint of the individual presenting Bill Smith’s card to Smith’s template on file—is a quicker process than searching an entire employee database to make a fingerprint match.

The process can still take several seconds, including the time needed for an individual to place a finger correctly on a small glass platen for reading, or to stop and face a camera for an iris scan, for instance. Consequently, says Peterson, biometrics are rarely used at the primary entry gate to a factory, because the throughput doesn’t allow it. “You’d have people backed up trying to get to work, and management would never go for that,” he notes. Instead, biometrics are more often used at higher security levels, for access to expensive equipment or tool rooms, or to control rooms, for example.

At Honeywell Process Solutions (HPC), Phoenix, Leslie Arnold notes that one of Honeywell’s process customers whose facility is located on a shoreline has tied the use of biometrics to the U.S. Coast Guard’s system of Maritime Security (MarSec) threat levels. Linked to the Department of Homeland Security’s Homeland Security Advisory System, MarSec levels reflect threat levels in the marine environment, ranging from Level 1 at the lowest threat level to Level 3 at the high end.

“As the MarSec level moves from 1 to 2, the people at the site are required to use a biometric, along with their access cards,” explains Arnold, HPC’s marketing and business development manager for industrial security solutions. “What we’re doing is just double-checking to be sure that each person is who they say they are. What we’re using at this particular site is a hand geometry reader,” Arnold says. “It takes quite a bit of time for people to use a biometric, as opposed to just a card, so you don’t want to do it on a day-in and day-out basis, unless there’s a need.”

See the story that goes with this sidebar: Making Security Pay