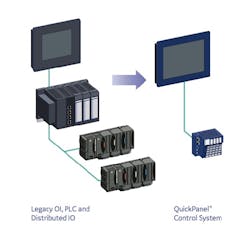

Looking at recent industrial machinery products, it’s clear that many OEMs have shifted away from the use of control systems with rack-mounted PLCs or PACs, pilot lights, gauges and push buttons, and now prefer the use of operator interface (OI) panels in place of other panel mount components. And it’s no surprise as to why they've done this considering the obvious benefits of reduced wiring costs and ease of shipping equipment in modular sections using distributed I/O. Plus there are the maintenance benefits for OEMs providing remote maintenance services.

To better understand this trend and see if any functionality tradeoffs are being made that could affect end users, I spoke with Vibhoosh Gupta, controls product management leader at GE Intelligent Platforms.

“Automation panels can significantly reduce software development costs,” Gupta says. “Many automation suppliers also tout the benefits of a shared database between the PAC and the OI panel. The benefit of having this shared database is that, if these are separate devices, they will have separate databases—meaning that each time you add a variable, you need to download to both devices. If the controller and OI get out of sync, you end up with communication errors and possibly unexpected operation. Automation panels, with their use of a single database provide a single development environment and a single library for reusable objects.”

While it may seem counterintuitive, combining the PLC and OI into a single device can “actually improve the update times for the operator interface in many applications,” Gupta says. “This is because one of the main CPU tasks for a traditional OI is communications with the controller. When today’s operators press a button on the OI screen, they expect an immediate response for the equipment and immediate feedback on the graphic screen. The biggest reason for delays in that response is the communication driver between the OI panel and the PLC. With an automation panel, this communication is much faster, because it is internal to the device. There is no need to rely on serial or Ethernet communication links for updating operator screens.”

Hardware costs are also reduced with the use of an automation panel, Gupta says. “Combining the controller, operator interface, and remote connectivity into a single device means there is only one device to purchase, install and configure. This saves money on both production time and on panel space.”

You may be thinking at this point it’s only natural that Gupta thinks automation panels are great—after all, the company that employs him sells lots of them. Gupta is quick to note, however, that automation panels are not always the right choice for an OEM. “If the control system requirements are consuming the vast majority of the CPU time, then the operator interface performance can suffer because it runs at a lower priority than the control.”

He also points out other advantages to using separate programmable controllers. These reasons include faster control system performance, modularity, and the requirements of high availability systems.

“Many control applications have performance requirements that cannot be met by a single processor on an automation panel. For example, the GE QuickPanel+ has a 1GHz CPU and up to 1GB RAM. This enables the QuickPanel+ to perform as well or better than many low- to mid-range PLCs even while handling the operator interface requirements, but clearly a PAC controller with a 1GHz CPU is going to outperform an automation panel with a 1GHz CPU in terms of logic scan rate. If an application needs logic scans in the 10mS range, this can be a delicate balancing act for an automation panel while allowing adequate CPU resources for the operator interface functions. Also, larger systems may exceed the needs of the single CPU because of a specific combination of logic performance, graphics, data logging, and other tasks. In such applications, a separate PAC controller is the obvious choice.”

High availability systems that run 24/7 without interruption are a great example for keeping the controller and OI separate. “These high availability systems typically use hot-standby, redundant CPUs with synchronized scans to avoid a system shutdown if a single component fails,” says Gupta. “Hot-standby control is not as common in automation panels. However, if the touchscreen or display fails, the system will continue to run. At that point, the OI functionality could be operated through a remote web browser on a PC, or the system could automatically go into a controlled shutdown sequence. Either way, the automation panel would need to be replaced and would eventually require a system shutdown. With hot-standby CPUs on a PAC controller, the failed component can be replaced while the system continues to operate from the backup CPU, so no downtime is typically required.”

Realiability is another factor that must be considered when making the decisions to keep the OI and controller separate or use an automation panel. “Most programmable controllers have a well-earned reputation for reliability,” says Gupta. “Operator interface products have not historically had the same reputation. Resistive touchscreens wear out over time. The display backlight eventually fades or burns out. The screen can become damaged due to environmental exposure.”

While all these issues can be cause for concern, Gupta says “none of these problems would interrupt the controller itself from running and updating the inputs and outputs.”

To see a demonstration of how this scenario plays out, see the video below from GE-IP. In this video, a GE QuickPanel+ experiences catastrophic screen damage, but the QuickPanel+ is controlling the red flashing light in front of the panel, demonstrating that the control system continues to function in spite of the damage to the screen.

“If the touchscreen or display gets damaged or fails, you will need to eventually replace the automation panel, but the control program will continue to run,” says Gupta. “The unit in the video is still operational and the operator screens are fully functional through the built-in web browser.”

About the Author

David Greenfield, editor in chief

Editor in Chief

Leaders relevant to this article: