It’s been a decades-long quest, but manufacturers finally are finding reliable methods of moving data from plant-floor devices and applications to enterprise-level systems. Even more important, they also are learning how to turn much of that data into information that can be used to drive business decisions.

“Roughly 75 percent of manufacturing execution system (MES) users and more than 50 percent of control system and advanced application users, as a whole, are doing some form of enterprise integration,” says Maryanne Steidinger, director of product marketing, asset, operations and information software at Schneider Electric. “This has been going on since MES was developed in the mid-1990s. It’s real, and in today’s business environment, it’s required.”

Industry analysts argue that linking plant-floor and higher-level systems gives manufacturers a form of intelligence that’s necessary to keep pace with constantly changing market dynamics. ARC Advisory Group coined the term “manufacturing intelligence” to describe the type of information these connections produce. Another analyst firm, IDC Manufacturing Insights, calls it “operational intelligence.”

Lorenzo Veronesi, a senior research analyst for IDC Manufacturing Insights, recently authored a report outlining why and how manufacturers are collecting and using the information that comprises operational intelligence. The August 2014 report, “From Data to Actionable Information: Improving Operational Processes by Deploying Operational Intelligence,” was commissioned by PT Solutions, a UK-based supplier of industrial IT solutions.

“The end goal [in creating operational intelligence] is to improve customer fulfillment by linking plant-floor operations with customer needs,” Veronesi says. But, as his report outlines, customer needs are not always easily met, which is why Veronesi sees the entire manufacturing sector moving toward the “intelligence-intensive factory of the future.”

Operational intelligence will be necessary, Veronesi contends, because the days of a manufacturer being able to differentiate itself in the marketplace based on a single factor—such as consistently offering customers either the lowest price or the highest-quality product—are waning. Instead, all manufacturers will be expected to offer high-quality products at reasonable prices, and doing so successfully will require ready access to production data across the enterprise.

The factory of the future, according to Veronesi, will be “underpinned by IT and operations technology creating real-time decision-making environments, enabling operations teams to improve and speed up their decision-making.”

Industry experts—analysts and vendors alike—have been predicting these types of outcomes since the first MES system debuted more than two decades ago. However, the current reality of plant-floor-to-enterprise system integration does not always match those early prognostications.

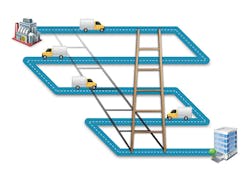

Most of the early visions involved data moving in a straight line—from plant-floor devices, to MES systems and then to enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. But as manufacturers started implementing these integration projects, there were times when that straight line diverged based on an individual company’s needs.

Sometimes this divergence happened at the enterprise-system level, with the data being directed to a supply chain planning or product lifecycle management system rather than ERP. Other times the data remains at the MES level, but is shared across departments, and/or facilities, across the enterprise.

As they’ve become more aware of manufacturers’ desires to share plant-floor data across the enterprise, technology vendors have responded in a variety of ways.

One of the first steps was forming industry consortia to develop standard methods of connecting applications from different vendors. The logic behind this move was that a greater number of manufacturers would be willing to purchase new technology—thus generating greater potential profits for all vendors—if the manufacturers knew it would be easy to fit the newly purchased systems into their existing plant infrastructure.

The OPC Foundation has been at the forefront of this standardization movement since the mid-1990s, when it released its first set of specifications for exchanging data between plant-floor applications. This was around the time that software engineers discovered that the graphical user interface that made Microsoft Windows the de facto standard for office PCs would also work well for displaying plant-level data.

With that in mind, the OPC Foundation harnessed Microsoft’s Distributed Component Object Model—widely known as COM/DCOM—to create a set of standards for exchanging data between plant-floor automation and control applications from various vendors. These early standards focused on three types of data exchange:

- Sharing process data such as values, time and quality information across systems;

- Making sure alarms and event data could be distributed among different applications; and

- Creating uniform methods for pulling historical data from various plant-floor databases.

These specifications were adopted by a large segment of the automation and control vendor community, making it easier for manufacturers to build plant-floor information systems. However, as OPC Foundation President Tom Burke pointed out in a recent Automation World webcast, these early specifications only supported the exchange of data among systems located on the same control network within a specific facility. That limitation prevented them from facilitating true plant-floor-to-enterprise integration.

Application-level linking

The OPC Foundation addressed that issue by developing a new set of standards called OPC UA—or Unified Architecture—that can carry data, in secure fashion, across Internet-based networks.

More than 3,600 automation and control vendors have made their applications OPC UA-compatible, according to the OPC Foundation. Manufacturers that use these applications can develop processes that involve moving data between applications from different vendors, and then extend those processes to include multiple facilities within the enterprise and even supply chain partners.

InduSoft has enhanced the value of its Web Studio application development platform by making it OPC UA-compliant, according to Scott Kortier, an InduSoft senior technical salesperson.

“Web Studio has built-in drivers that connect industrial PCs to PLCs or other devices, but we don’t have drivers for every device on the market,” Kortier explains. “In cases where we don’t have drivers, we connect with that device through OPC. Data goes to an OPC server, which is a piece of software that acts as a translator. It speaks the proprietary language of the device and translates it to language that Web Studio and other applications can understand.”

Though OPC offers a proven method for linking plant-floor and enterprise systems, it’s not the only strategy technology vendors have adopted for making such connections.

For instance, ERP software giant SAP now has its own set of manufacturing applications. It also offers its customers multiple methods for linking plant-floor devices with those applications, as well as for sending data to applications within its flagship SAP Business Suite.

A product called SAP Plant Connectivity incorporates OPC UA into a platform for connecting plant-level devices with SAP applications. However, users also can employ proprietary SAP technology for making those connections if it suits their needs.

Meter manufacturer moves data

A project at Elster, a global manufacturer of smart meters for gas, electric and water utilities, illustrates how OPC UA supports the flow of data from plant-floor to enterprise-level systems. Elster created an OPC UA-based network for moving data from PLCs attached to production machines to its SAP MES.

Elster had well-defined goals when it launched this project, starting with being able to collect precise traceability information to help its customers comply with product liability requirements in the 100-plus global markets it sells its meters in.

The first step in the project involved attaching PLCs from Beckhoff Automation to specific machines on the Elster production line. Beckhoff embeds OPC servers in all of its devices, so selecting that brand of PLCs provided Elster an open channel for communicating with other devices and systems.

Because data would be moving from the Beckhoff PLCs to SAP’s MES, Elster chose SAP’s Plant Connectivity platform as its communications channel. For this project, Elster’s PLC programmers instructed the PLCs to collect specific test data on each part that passed through the production line, and pass the information to the MES.

The MES used that data to determine whether parts could move to the next phase of production or be sent back for rework. In addition to providing the traceability information Elster wanted, this connection provided an additional tool for monitoring overall product quality, as well as a method of creating key performance indicators (KPIs) that could be used to drive continuous process improvement.

Roland Essmann, Elster’s project manager for MES and manufacturing IT, said Beckhoff’s and SAP’s use of OPC UA in their products factored into the project’s success. “The SAP ME system, with its web-based graphical user interface, was easy to use,” Essmann said, “and it was extremely easy to connect it without our shop-floor devices via OPC UA.”

Integration infrastructures

Vendors with roots outside of ERP also have created their own enterprise integration infrastructures. Product lifecycle management software supplier Dassault Systèmes has created a method for bringing plant-floor data into the product development process through a series of acquisitions.

Dassault’s process started with the purchase of Delmia, which has solutions for simulating product designs and programming machines that create parts prior to product assembly. Over the past two years, Dassault has expanded its footprint even further by purchasing automation and controls software supplier Apriso, and a supply chain planning and execution software company called Quintiq.

The Apriso/Delmia integration is achieved through the use of embedded business process management (BPM) technology, says Tom Comstock, Apriso’s executive vice president of product marketing. “This means each application shares a common data model, enabling them to work with other applications.”

In addition to having its own BPM-based integration infrastructure, Comstock says Apriso also supports various proprietary methods of integration with major ERP solutions, such as SAP and Oracle.

Tractor maker plows data

Apriso’s support of SAP’s integration technology helped AGCO, a global supplier of agricultural equipment, record substantial operational improvements at one of its tractor plants.

An integrated Apriso-SAP solution was implemented in a plant that had recently adopted Lean production principles. While the Lean methodologies already had contributed to operational improvements such as lower inventories, higher product throughput, less scrap and fewer product quality issues, AGCO management was able to attribute additional positive metrics to the links forged between its MES and ERP systems.

The most telling of these metrics was a reduction in takt time, a term associated with Lean principles. Takt time is a measure of how long each operation in a manufacturing process must take to ensure that products consistently meet customers’ expected delivery dates without keeping excess inventory on hand. In addition to bringing AGCO’s takt time to less than 10 minutes, the MES-to-ERP connection contributed to the following metrics:

- An 8 percent boost in assembly line productivity in the first year, with projections of 25 percent to 30 percent increases over the first three years.

- An improvement in overall equipment effectiveness (OEE) by 22 percent in a core machining area.

- An increase of the number of new products introduced each year.

Schneider Electric, well known as a supplier of automation and control devices, also has been on an acquisition spree during which it assembled a portfolio of software products that monitor and control automation processes. One of these acquisitions was of Invensys—a company that had also absorbed several automation software companies, including InduSoft and Wonderware. The latter two brands both have their own platforms for distributing plant-floor data across the enterprise.

Wonderware was among the first automation software vendors to fully embrace the Microsoft technology, and its solutions remain primarily based in that environment. Similar to Apriso, Wonderware says its products are equipped to let users follow BPM principles when creating methods for linking systems and moving data across an enterprise.

F&N Dairies, a Malaysian company that produces and sells packaged beverages with household names such as Carnation milk and Sunkist juice, used two Wonderware products to make one of its plants fit the IDC Manufacturing Insight description of the intelligence-intensive factory of the future.

By connecting the Wonderware Historian industrial database with the Wonderware InTouch HMI application, F&N created a manufacturing operations solution that it calls Process Nexus II.

Before installing this system, F&N personnel entered and tracked all process data manually. “After the Nexus II implementation, it is very convenient to summarize and consolidate the plant data,” said Sitthichai Sribunyapirat, F&N production manager. “We are now able to collect product traceability information for both the upstream and downstream functions of our process in real time.”

The system also has improved F&N’s ability to manage its inventory. Historically, F&N sent finished product to a warehouse where it waited to be transported to ports for distribution to customers across the globe.

With the Process Nexus II system in place, finished product is now sent directly to container vans, ready for transfer to the ports for distribution, bypassing the warehouse altogether—a fitting development for the factory of the future.

About the Author

Sidney Hill

Automation World Contributing Writer

Leaders relevant to this article: