The shale oil industry has taken off like gang-busters, with major shale gas formations being tapped around the U.S. It’s like the Wild West—oil companies drilling wells as quickly as they can. The days of easy oil are gone. But in the past decade, technologies have been developed that enable oil producers to go after unconventional resources like shale reserves, with directional drilling, microseismic technologies and multi-stage fracturing, to name just a few.

“Those technologies all came together to go after vast resources that we obviously have here at home and abroad as well,” says Chris LeBlanc, vice president of sales and marketing for Lime Instruments (www.limeinst.com), which provides custom high-volume control systems primarily in the shale stimulation and production space. “But it’s very economically difficult to get to.”

Gathering those reserves economically and safely requires a level of automation that is not there in many cases. Although some drilling and exploration companies are taking advantage of leading-edge control and automation technologies, much of the industry still uses fairly basic automation, focused primarily on safety and uptime, with little in the way of yield and throughput optimization.

This is true at the drilling and production stages alike.

“Automation is pretty basic, especially at the wellhead, but even at some of the process plants that it’s being pulled back to,” says Brandon Spencer, vice president of chemical, oil and gas for the U.S. at automation provider ABB (www.abb.com). Many of those control systems are still based on PLCs rather than DCS, he notes.

A more strict regulatory environment and more public scrutiny in the downstream end of the industry has led to more automation and control there, according to Lee Swindler, program manager for system integrator Maverick Technologies (www.mavtechglobal.com). “In contrast, midstream and especially upstream, they’re more cowboys,” he says. “There’s not the same level of discipline, same level of maturity. That extends into the automation side as well.”

Frank Whitsura, vice president and general manager ofprojects and automation solutions for Honeywell Process Solutions (HPS, www.honeywellprocess.com), likens today’s shale gas industry to the refining industry some 30 years ago—with a lot of disparate units, immature control, and low throughput and yield. “If you look at the shale gas landscape today, it’s actually in a very similar condition,” he says.

But the industry is on the verge of a technology explosion, says Jerry Hines, North American oil and gas manager for National Instruments (www.ni.com). Many Tier 1 and 2 companies have been feeling the effects of the multitude of smaller companies chipping away at their marketshare, he says. “They’re implementing new technologies, and moving away from the proprietary, more complex systems they have.”

Drilling needs

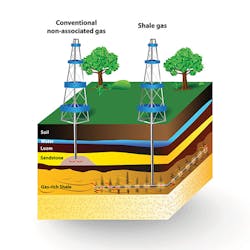

Conventional well drilling uses enhanced recovery methods, such as gas lift, only when the wells become mature. Shale drilling is a different story, however. Because the oil is coming out of the cracks in the shale, it loses its pressure by the time it comes out, so almost 80 percent of the wells apply gas lift techniques that add gas pressure to help the oil and water come up faster, explains Sudhir Jain, an oil and gas consultant for Emerson Process Management (www.emersonprocess.com).

Rod pumping—a basic technique that is the most common form of lift—can be controlled by time, or by measurements and calculations. “That was probably the first thing our industry ever used automation for,” says Rachel Phillips Herrick, a production engineer at Goodrich.

Petroleum, an independent oil and natural gas exploration, development and production (EDP) company. Plungerless techniques are the cheapest form of artificial lift the industry has, she adds. “It’s a simple piece that brings the water back up. It’s controlled by time, or you can go more digital and control with pressures and rates, and pressure differentials.”

Closed-loop control would make gas lift techniques more successful, Jain says. “This is not being done anyplace right now, but I think that’s the future,” he says, describing setpoint measurements that could help optimize the flow, and also see how much water could be disposed in the process. “This is the future, which we do very successfully right now on the platforms.”

Drilling companies need to be careful not to damage the wells, which has a tendency to happen with artificial lift, Phillips Herrick says. “We can’t draw down too much or else we will damage the reservoir. We have to baby the well and have complete control of the pressure,” she says. “Imagine banging on concrete until it breaks up into little bits. It will obstruct the well flow. This is especially important in the first year. We can prevent that from happening with this high-resolution data.”

Measurement of pressure and flow rates are very important for reservoir analysis, Phillips Herrick says. Goodrich uses data from previous wells to improve on drilling of future wells. “It’s all analogy-based. We have equations that we can apply to form our conventional knowledge to this,” she says. “We have tight curve data from the first few wells and we can make this one better.”

Midstream control

High-resolution data is essential at the stimulation and production stage also. “Monitoring the well after it’s been brought on is another area where there’s going to be a lot of room for growth,” NI’s Hines says. “Right now it’s fairly unautomated. They rely on people to travel to the well sites and spend a couple of days there in a lot of instances. Being able to do that remotely and put instrumentation there permanently is an area where we see a lot of focus in the mid to long term.”

>> Click here to read how automation can remove the risk of shale oil safety.

Lime Instruments, a key partner with NI, provides its control systems mainly for third-party exploration companies. At the cutting edge of asset and process monitoring, its highly networked equipment is sampling instruments a minimum of 10,000 times a second, LeBlanc notes.

Although such fast sampling rates might not be needed to find regularly recurring problems, they’re essential for spotting the intermittent ones. “When it comes to data, faster is better, but there’s a sweet spot. Right now that’s around 10,000,” LeBlanc says. “If you’ve got a problem, you need to see that there’s a 4 ms hit of information. You’re not going to see it unless you’re sampling it fast enough.”

A typical shale well site that Lime Instruments is involved with will have 20 to30 pieces of heavy equipment, “all networked together, all acting like one giant instrument. Everything is distributed, but executes as if it’s one instrument,” LeBlanc explains. Although any given pump or blender could be monitored on its own, of course, “the real value is when you bring it all together,” he says.

The data is monitored primarily to keep all the equipment running at optimal levels—to improve uptime and safety, and to get the most oil possible out of the ground. “With the current shale plays that you have, the zone is so narrow, the control of the treatment has to be very precise,” LeBlanc says, explaining that too much pressure in the well will expel too much of the very expensive raw material at once, but pressure cannot be taken too low either. “It has to be very precise. They need better, tighter, more repeatable control.”

As in many industries, shale players are concerned about data overload, so are focused on relatively simple data points from the well, including flow, temperature, pressure, etc., Spencer says. “They’re trying to get some more statistics, looking at the productivity and efficiency of the process,” he says. “They pull some of that data back to central locations to see what’s going on with one well vs. another, or one production unit vs. another.”

Right now, much of the data is being handled at a local level, Spencer notes. “But we’ve had meetings with the majors lately, and they’re interesting in going from smaller units and smaller processing plants to more centralized locations, with larger processing plants. They’re beginning to have more in common with offshore installations.”

Still evolving

There’s a lot of innovation going on in the shale industry right now, but there are still areas where improvement can be generated.

More sophisticated users are beginning to focus more on optimizing the upstream process, Maverick’s Swindler says. “Particularly if they have downstream operations, they have seen what’s possible, in that there’s money on the table,” he says. “They realize if they could bring some of those best practices from downstream, they could be more efficient and make more money.”

Moving forward, shale oil producers will be able to make better use of the data for preventive maintenance purposes. “It is the future,” LeBlanc contends. “It’s not an easy application to solve, to be quite honest, especially in this rough environment. But it is definitely the future.”

Typically, a service company could have 15 pumps on a job. Because uptime at the well site is so vital to their survival in this industry, they keep two or three pumps as backup at that site, and each of those pumps costs more than $1 million. Meanwhile, they might have to say no to another job because they don’t have enough pump horsepower in reserve. If they could predict and monitor the health of the pumps they’re using, they wouldn’t require as much backup, and could put some of those backup pumps on the other job instead.

The centralization of data—and what they do with it—will also be very important, Spencer says. “They say, ‘We applaud all the data you can give us, but you’ve got to help me figure out how to do something with it,’” he says. “They need to not just be reactive, but be proactive to it.”

Everything is progressing the way you’d expect, Swindler says, given that shale is still on the upswing of the boom cycle. “Once it matures, trying to get the most out in the most efficient way will become more important than speed.”

The shale industry is not slowing down yet, though. The sense of urgency is still very aggressive, Spencer notes, but the producers are also beginning to look further into the future. “They still have their foot on the gas, but they realize this plant is going to be here for the next 10 years,” he says. “So now it’s: Run as fast you can, but while you’re running, look around for technologies.”

About the Author

Aaron Hand

Editor-in-Chief, ProFood World

Leaders relevant to this article: